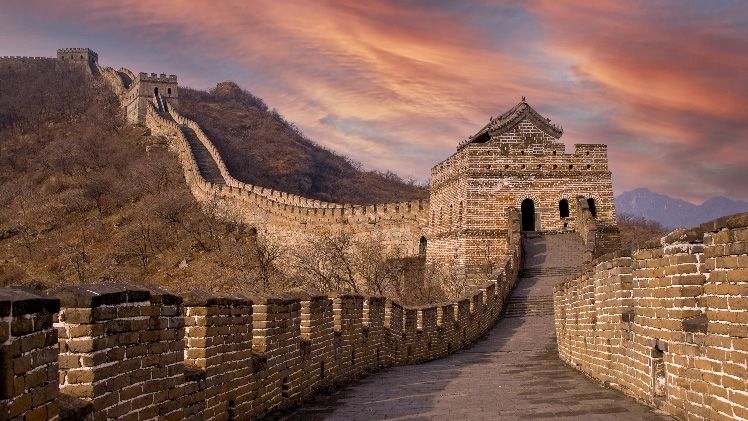

China – The long road to transition

- 2023.21.11

- 0

- Download the publication (PDF - 1,10 MB)

- What will drive growth in the future?

- China's strengths

- Changing priorities for the Chinese government

In summary

China is undeniably in the midst of a slowdown. After twenty years of robust, uninterrupted growth, this slowdown was not unexpected, but has proved too fast and strong relative to the trajectory projected by both the Chinese authorities and the rest of the world. While no one doubted China's ability to become the world's leading economic power prior to Covid, this prospect is growing more remote and convergence is once again becoming an issue. What is certain is that China's development path will be less straightforward than that of Japan, Korea or Taiwan at the same stage of development, as its potential growth is diminished by its size and the current geopolitical situation.

China still boasts undeniable strengths, in particular a unique industrial and logistics complex that has fuelled a growth model based on foreign trade and infrastructure investment. However, this model is no longer suited to current balances. Amid slowing global demand for goods and reorganization of value chains (which is unfavourable for China), the question of the transition to domestic-driven growth is becoming more acute.

Although this rebalancing act is necessary, however, it looks all the more difficult given that the country's extensive real estate crisis is weighing on household confidence, already been severely shaken by three years of zero-Covid policy and by the perception that economic growth is no longer the top priority of government authorities.

The major stimulus package that was expected did not materialise, taking everyone by surprise, but especially domestic players which had become accustomed to massive liquidity injections during downturn phases: the priorities of the public authorities and Xi Jinping have changed. The most recently announced economic support measures (budget deficit up from 3% to 3.8% of GDP) showcase a slightly clearer interest in stabilising growth, but remain very far from what was put on the table in 2008 (the plan is four times lower in terms of debt issuance). These measures continue to target infrastructure investments, while consumption has become the Achilles heel of the Chinese economy.

Sophie WIEVIORKA, Economiste - Asia (Excluding Japan)